Slava is that brand you often tend to overlook in the beginning of your Soviet watch collection journey. It doesn’t have Raketa’s appeal and Vostok’s popularity. Then you randomly add one of them to your collection, then another… and you end up with a whole watch box of these usually more affordable timepieces with such unique designs (any other Soviet watches with an asymmetric case?). You instantly recognize these double barrel movements, and you quickly learn that even a freshly serviced Slava may need a service again very soon. In this overview we’ll talk about the history of the Slava watch brand and we’ll have a look at the most iconic Slava watches.

Table of Contents

Second Moscow Watch Factory: Origins and Evolution

The Slava brand traces its origins to November 29, 1924, when the Moscow Electromechanical Factory (MEMZ) was established within the Military-Technical Administration of the Red Army through a merger of the Moscow radiotelegraph factory with electromechanical and watch workshops.

The newly established factory occupied a renovated three-story stone building near Tverskaya Gate, starting with just 125 production workers. Initially, MEMZ wasn’t producing personal timepieces at all – instead, workers focused on repairing and manufacturing telegraph equipment, radio stations, projectors, and maintaining electric secondary clocks for the Moscow tram system.

After several organizational changes, the factory’s destiny changed dramatically in autumn 1927 when it was transferred to the Precision Mechanics Trust (Tochmekh). This marked the beginning of MEMZ’s transformation into a clock and watch manufacturer. By late 1927, the factory began assembling alarm clocks from imported components.

The crucial decision came on December 20, 1927, when the Council of Labor and Defense issued a resolution “On the Organization of Clock Production in the USSR,” calling for a factory capable of producing 500,000 pocket watches and 500,000 large clocks annually.

On April 25, 1930, MEMZ was officially renamed the Second State Watch Factory (the “Second” designation indicated it came after the First State Watch Factory, established earlier in 1930). This marked the birth of what would eventually become the Slava brand. After the war, the reinstated Second Watch Factory shifted focus toward wristwatch production. The factory underwent several rebranding phases: in 1958, it was officially renamed the Second Moscow Watch Factory, and in 1964, it was rebranded again to “Slava” (Слава, meaning “glory” in Russian). From this point forward, all watches produced at the facility bore the Slava name on their dials.

Foreign Technology Transfer

A significant development in the factory’s early history came from an ambitious technology acquisition program. In 1928-1929, Soviet officials traveled to Western Europe and America to study clock manufacturing and purchase equipment. European companies proved reluctant to cooperate with the Soviet industrialization efforts.

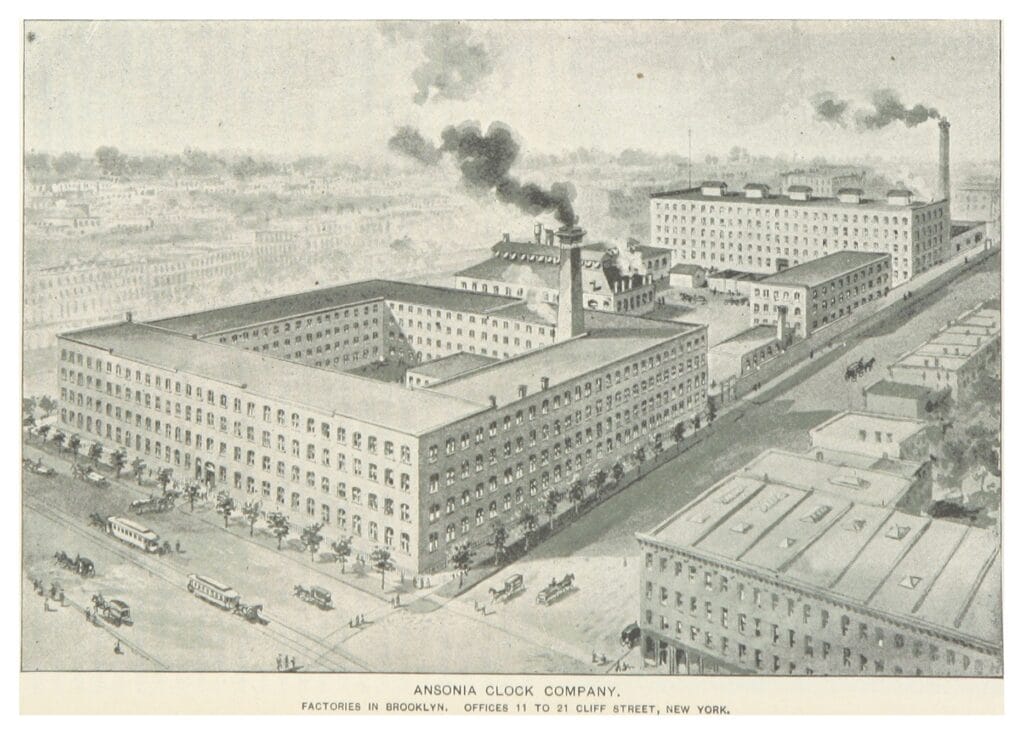

American companies showed more willingness to sell their equipment, perhaps some of them were on the edge of bankruptcy and Russians paid in solid gold, not rubles. The Ansonia Clock Company of Brooklyn, New York, offered to sell their entire large clock and alarm clock factory, including hundreds of machines, blueprints, and tooling. Similarly, the Dueber-Hampden Watch Company of Canton, Ohio, offered a complete pocket watch factory capable of producing 200-250,000 pieces annually.

Soviet officials made the pragmatic decision to purchase this used equipment, reasoning that it was better to have functional machinery than none at all while the country built its industrial capabilities.

The equipment from Ansonia was designated for MEMZ (the future Second Moscow Watch Factory), while the Dueber factory went to what would become the First Moscow Watch Factory.

The technology transfers kick-started watch production in Russia: in 1933, the Second Moscow Watch Factory produced almost 4 million timepieces, most of them (3.5 million) being wall clocks. In 1936, 2SWF started producing pocket watches based on caliber K-43 inspired by Dueber-Hampden’s movement Size-16.

Later on, the Soviet watch industry also closely collaborated with the French Lip brand to acquire technology and equipment, which allowed many improvements to various movements produced by Soviet watch factories. “The Birth of Soviet Watchmaking” ebook describes those foreign technology transfers in more detail.

Wartime Evacuation and Military Production

The German invasion on June 22, 1941, dramatically transformed the factory’s operations. Civilian production of alarm clocks and pocket watches ceased almost immediately as the facility converted to military manufacturing. With many workers called to military service – approximately 200 joining the Moscow people’s militia – women and teenagers replaced the departing men. Working days extended to 12 hours under increasingly harsh conditions.

On October 20, 1941, as German forces approached Moscow, the Second Moscow Watch Factory began evacuation to Chistopol under State Defense Committee resolution. The massive relocation involved 170 railcars of equipment and 488 personnel, including 128 engineers and technical staff. The journey proved treacherous – while the first groups reached Kazan by November 1st, navigation on the Kama River had closed, leaving equipment stranded outdoors through winter.

The evacuation split the factory into two operations: the relocated facility in Chistopol (Factory No. 835) began producing magnetic detonators, grenade shells, and parachute deployment mechanisms, while a skeleton crew remained in Moscow. The Chistopol facility would ultimately become the Chistopol Watch Factory, home of Vostok watches. The Moscow operation, redesignated as Factory No. 853 under the Ministry of Mortar Armaments, focused on producing mechanical time fuses for anti-aircraft shells – sophisticated devices that used clockwork mechanisms to detonate projectiles at predetermined intervals.

By 1943, both operations were running effectively. The Moscow facility had grown back to nearly 2,000 workers and began resuming civilian timepiece production alongside military contracts. That same year, Factory No. 853 established a machine-building workshop to manufacture their own equipment.

The war period also saw the creation of the watch industry’s research institute (later NIIChasprom) in 1944, housed within the Moscow factory. This marked the beginning of more systematic technological development that would benefit post-war civilian production.

After the war, in August 1946 the Ministry of Mortar Armaments was abolished and on its basis the Ministry of General Machine Building and Instrument Making was created, in which Glavchasprom (Главчаспром: Main Administration of the Watch Industry) was formed. All watch factories of the country were subordinated to Glavchasprom, including the 2nd Watch Factory.

A Civilian-Focused Philosophy, 1950s – 1980s

Unlike other major Soviet watch manufacturers such as Poljot or Vostok, Slava watches were always intended for civilian consumption, without military or aerospace applications. This positioned the brand as the “everyman’s watch” of the Soviet Union – reliable, accessible timepieces for daily wear rather than specialized instruments for cosmonauts or military personnel.

In the beginning of the factory’s post-war period, wristwatches were assembled using parts produced on other factories. In particular, the 2SWF produced Zvezda watches from Penza Watch Factory supplied parts starting in 1947. In 1951-1954, Pobeda (Победа, “victory” in Russian) watches were assembled from parts produced at the First Moscow Watch Factory. In 1954, the Second Watch factory started producing parts for Pobeda watches in-house.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, Slava’s own production was primarily limited to ladies’ calibers, alarm clocks, wall clocks and stop watches. However, growing demand for men’s watches presented a challenge. In a uniquely pragmatic approach, Slava engineers solved this by placing smaller ladies’ movements in larger men’s cases, secured with spacers. While not ideal from a horological purist’s perspective, this stopgap solution allowed the factory to satisfy market demand while developing their own larger calibers.

The breakthrough came in 1966 when Slava designed its own line of caliber 24xx mechanical movements specifically for men’s watches. These movements featured a distinctive dual mainspring barrel system coupled with an idler gear, designed to release energy more evenly as the springs unwound – a unique approach in Soviet watchmaking.

In the same year of 1966, the factory was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labor for mastering new types of production, and a mechanical assembly complex with an area of 17,000 square meters was put into operation in Cheryomushki (South-West Moscow) three years later.

The 24xx series evolved over time with various complications:

- 1966 – Calibers 2409 (base movement) and 2414 (date complication)

- 1973 – Calibers 2427 (automatic day date) and 2428 (manual day date)

- 1989 – Caliber 2416 (automatic date)

| Caliber | Year | Stones | Height | Power Reserve | Auto | Date | Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2409 | 1966 | 21 | 3.8mm | 40h | - | - | - |

| 2414 | 1966 | 21 | 4.1mm | 38h | - | + | - |

| 2427 | 1973 | 25 | 6.85mm | 31h | + | + | + |

| 2428 | 1973 | 21 | 4.8mm | 36h | - | + | + |

| 2416 | 1989 | 25 | 6.12mm | 33h | + | - | - |

While innovative and commercially successful, these movements are generally considered less reliable than designs from other Soviet factories. This reliability issue may explain why Slava was among the first Soviet manufacturers to embrace quartz technology when it became viable for mass production in the end of 1970s.

Beyond wristwatches, Slava manufactured a comprehensive range of timepieces including stopwatches, pocket watches, alarm clocks, table clocks, and wall clocks. The factory’s 1976 brochure claimed annual production of approximately 8 million timepieces, indicating massive scale operations at their peak.

By the 1970s, Slava had developed into a massive industrial operation employing thousands of workers. The factory had evolved beyond a simple production facility into a comprehensive social ecosystem typical of major Soviet enterprises. The company maintained its own residential buildings for workers, holiday homes for rest and recreation, educational institutions including schools for workers’ children, and various social amenities. This reflected the Soviet model where large factories served as complete communities supporting their workforce in all aspects of life.

The factory’s mechanization and automation had reached impressive levels, with scientific labor organization and advanced technical achievements supporting the production of hundreds of different watch models.

Global Export Success

From the 1950s through the 1980s, Slava achieved remarkable international success, exporting up to 50% of their production worldwide. The expansion was impressive:

- 1955 – Exports began to 6 countries

- 1965 – Expanded to 36 countries

- 1979 – Reached 72 countries across all continents

A particularly interesting partnership developed with Italy in late 1980s, where Slava produced specialty watches for the Italian market featuring unique designs and case-backs stamped “CCCP” – clearly marketed as exotic Soviet timepieces for Western consumers. This partnership resulted in some of the most sought-after Slava models, including Slava California and Slava Watermelon.

Slava Vintage Watches: Iconic Models

Slava Tank

Massive and heavy, this watch is characterized by its rectangular case design that echoes the famous Cartier Tank aesthetic. Powered by the automatic 2427 movement, it usually comes on its specific bracelet. Plenty of color schemes available, there is a Slava Tank for everyone! A decent piece can be acquired for $100-$200 (or less if you don’t mind a few scratches).

Slava California

This watch is part of the end of 80s batch destined for the Italian market. “California” dial is a unique layout that combines Roman numerals on the upper half of the dial with Arabic numerals on the lower half. This mixed numbering system, which became popular in some luxury Swiss watches (Rolex in particular), was an unusual and sophisticated choice for a Soviet timepiece.

Slava Asymmetric Case

The Slava asymmetric case watch (also called “kosaya” / косая / oblique in Russian) represents one of the more avant-garde designs from the Soviet watch industry, featuring a distinctively offset case that creates a bold, modernist aesthetic. Again, a multitude of color schemes were available for this model. Unsurprisingly, this case is extremely prone to scratching, so finding one in pristine condition is a challenge.

Slava “Fridge”

This rectangular design is nicknamed “fridge”. Powered by the manual day-date caliber 2428, this is a very wearable watch which will for sure attract some attention. Unless you aim for a rare color scheme, $100 should get you a good example.

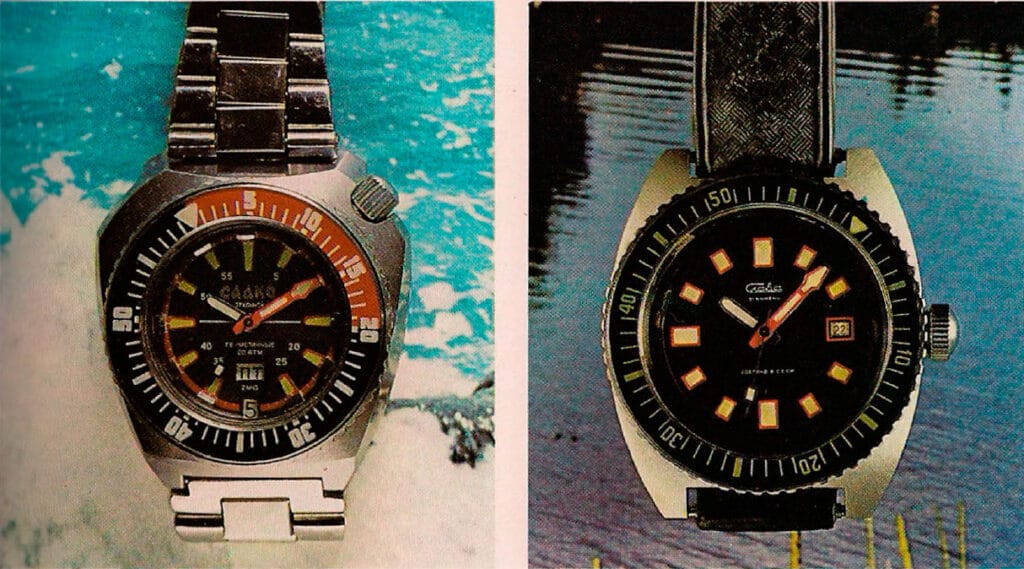

Slava Amphibians

As most other major Soviet brands, Slava designed divers’ watches – amphibians. The one on the left is called “Sadko” and is extremely rare. In the recent years, there were a few more or less successful reissues of this watch, the vintage original being nearly impossible to come by. The watch on the right is the “regular” amphibian and while rare, can still sometimes be found for sale.

Post-Soviet Decline

The collapse of the USSR proved devastating for the Slava brand. Like most Soviet industrial enterprises, the factory was privatized during Boris Yeltsin’s controversial privatization program of the early-to-mid 1990s. This process, described by some economists as “katastroika” – a combination of catastrophe and perestroika – resulted in the “most cataclysmic peacetime economic collapse of an industrial country in history”. The company struggled to survive.

The situation worsened in the early 2000s when the factory and the Slava brand were acquired by Globex Bank around 2005. However, this acquisition proved problematic when Globex Bank itself encountered financial difficulties. In a debt swap arrangement, the brand was transferred to the city of Moscow.

The original Slava factory building in Moscow was demolished in 2011 to make way for real estate development, marking the end of an era.

2019-Present: Renaissance Under New Management

A significant turning point occurred in 2019 when the brand was bought from the Moscow government, marking the beginning of its active development. The new ownership launched an ambitious revival program, releasing a large number of models in the premium segment.

The revival strategy included several key elements:

- Reissuing Classic Models: The company began producing reissues of bestsellers from the 1970s, 1980s, and post-Soviet period, appealing to collectors and enthusiasts who remembered the brand’s golden age. Amphibia “Sadko” is a good example.

- Limited Collectible Series: Special limited edition watches were created, including collaborations with famous personalities and brands. Notable examples include the “Little Prince” watch, which set a sales record when 700 pieces sold in just 7 minutes during pre-order.

- Cultural Collaborations: The brand partnered with Soyuzmultfilm for the “Yozhik Slava” watch themed around iconic Soviet animated films, and worked with watchmaker Anton Yaitsky on premium limited editions.

- Centenary Celebrations: In 2024, the brand celebrated its 100th anniversary with the launch of a dozen new models, including collaborations with renowned designers like Alexander Shorokhov for the “Revolution” collection.

Today, Slava operates as a modern watch company with a significantly different structure from its Soviet predecessor. The brand focuses on producing premium and collectible timepieces rather than mass-market watches. Current production utilizes both original Slava 2427 movements from remaining stock and newer movements from Vostok.

The company has established a strong online presence through its official website slava.su and maintains retail partnerships worldwide. Modern Slava watches are positioned as luxury items, with prices ranging from around $100 for basic models to over $1,000 for limited editions.

The brand has also embraced its heritage through museum initiatives, including exhibits at the Museum of Time and Watches in Moscow, and maintains active relationships with watch collectors and enthusiasts through clubs and events.

Slava’s Legacy

The Slava brand exemplifies both the achievements and challenges of Soviet industrial planning. At its peak, it successfully democratized timekeeping for Soviet citizens while achieving impressive export success. However, its post-Soviet struggles also demonstrate how quickly a respected brand can lose its reputation when quality control and trademark protection falter.

For watch enthusiasts, genuine Soviet-era Slava timepieces remain fascinating examples of pragmatic engineering – watches designed not to conquer space or time the depths, but simply to serve ordinary people reliably and affordably. In many ways, this makes them the most “honest” of Soviet watch brands.

References

- slava.su, “History of the Slava watch factory” (in Russian), book published in 2002 by Vladimir Bogdanov who worked at 2MWF as Chief of Quality Control Department.

- wikipedia.org, “Slava watches”

- dzen.ru, Series of two articles about Slava watches (in Russian)

Vintage Watch Inc

Dennis is the founder and editor of Vintage Watch Inc. Passionate about Soviet and Japanese vintage timepieces and a finance professional by day, he proudly wears a Seiko Pogue with his suit.